Why St Mary's Binsted is Special

Watch the short film about Binsted church's fascinating features by historian Martin D.W. Jones

Read an article by Martin Jones about this Grade II* listed church

Introduction

For a small single cell church, St Mary’s punches well above its weight. Historically, it holds unusual evidence of the violence of the Reformation and Victorian industrial technology.

Architecturally, its Romanesque font and wall painting fragments are important in their own right while the complex influences they illustrate add additional significance.

The 1867-1869 restoration encapsulates perfectly the ideas of Sir Thomas Graham (“Oxford”) Jackson RA (1835-1924), a major later Victorian / Edwardian architect whose work is now increasingly being appreciated. Key elements were innovative architecturally (the vernacular chancel arch), artistically (the sunflowers in the East window stained glass) and technically (the glass chancel pavement).

The Romanesque parish church

The church’s 12th century origins are seen in two small chancel lancets without scoinson arches, the piscina, the font and wall paintings. The importance of Binsted’s font is shown by the references to it in specialist works [e.g. Bond’s Fonts and Font Covers (1908), Harrison’s Notes on Sussex Churches (1911), Bowyer’s The Evolution of Church Building (1977).] as well as in general “tourist” literature. [e.g. Brabant’s Sussex (1906), Penguin Guide to Sussex (1957).]

Appropriated by nearby Tortington Priory soon after its construction, surviving features exemplify the variety of associations influencing parishes. Some are to be expected. The style of the font suggests links with stone carving in the Boxgrove area of West Sussex. [‘Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture’.]

Other features challenge “obvious” connections.

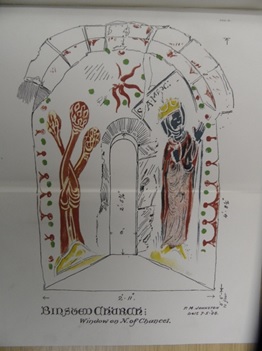

The wall paintings are now judged not to belong to the famous Lewes Group. Rather, the depiction of St Margaret is seen as similar in style to figures on the lead font at St Margaret of Antioch, Lower Halstow, Kent, dated to c.1190. [Park, ‘The Lewes Group of Wall Paintings in Sussex’, p.201.]

The English Reformation and the stripping of the altars

The sawn-off stumps of the probably early 14th century rood screen in the north and south walls enhance powerfully our understanding of the English Reformation. Historical scholarship now puts material evidence centre-stage in investigating the Reformation’s contours. Primary visual evidence of the destruction of specific forms of worship, and the theological belief system underpinning them, is rare in Sussex. Binsted allows us to glimpse first-hand the dramatic physical changes that the Reformation forced on England’s parish churches.

Victorian restoration and reconfiguration

Victorian restoration and reconfiguration

The major restoration in 1867-1869 by T. G. Jackson exemplifies perfectly his Ruskin-influenced working credo that architects are artists, that the arts must be reunited and that craftsmanship must be revived. Everything was a bespoke design by Jackson and, apart from a chancel screen, everything survives intact. The fixtures and fittings are of a very good quality, whether made locally or by the great firm of James Powell and Sons, Whitefriars. Carried out along superficially Camdenian Ecclesiological lines, three elements speak to significant changes at work in mid-Victorian church architecture. These are (1) the timber chancel arch, (2) the East window’s stained glass and (3) the glass chancel pavement. [Jones, ‘How “Oxford Jackson” began’, forthcoming.]

(1) The nominal chancel arch is an important example of the start of the breakdown of Camdenian Ecclesiology. For an architect to effectively do without a chancel arch shows an overthrow of Pugin and his heirs to grapple with the problems of visibility, audibility and spatial unity that so worried high church and low church alike. 1868-69 is a very early example of this. Furthermore, the way Jackson did it, using timbers as if the structure was a barn, is an early example of ‘the relaxing or vernacularizing of Gothic’ that occurred in the 1870s and 1880s. [A. Saint, ‘The late Victorian church’, p.20.]

(2) The ‘Good Shepherd’ panel in the East window contains an extremely early depiction of sunflowers for either the Arts & Crafts Movement or the Aesthetic Movement. This is five years earlier than the date usually given form its first appearance (1874 at Norman Shaw’s Lowther Lodge and J. J. Stevenson’s Red House, Bayswater). The panel was designed by the important stained glass artist Henry Holiday (1839-1927) and made in 1869 by the major firm of James Powell & Sons, Whitefriars to Jackson’s direction. [V&A, Powell Window Cash Book 1868-1872, p.97.]

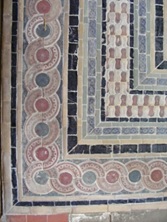

(3) The glass chancel pavement speaks of the love for industrial innovation so central to the Victorian world view. Equally, it is a major example of the industrial experimentation and technical virtuosity by James Powell & Sons, Whitefriars. In 1869, they discovered how to make ‘a form of opaque stained glass, composed of vitreous sheets which [could be] cut, painted and fired before being fitted together and cemented to a rigid backing’. [Hadley, ‘OPUS SECTILE. Art from Recycled Scrap’ (2014), p.1.]

(3) The glass chancel pavement speaks of the love for industrial innovation so central to the Victorian world view. Equally, it is a major example of the industrial experimentation and technical virtuosity by James Powell & Sons, Whitefriars. In 1869, they discovered how to make ‘a form of opaque stained glass, composed of vitreous sheets which [could be] cut, painted and fired before being fitted together and cemented to a rigid backing’. [Hadley, ‘OPUS SECTILE. Art from Recycled Scrap’ (2014), p.1.] Jackson was among its earliest champions and at Binsted in 1869 was the first to use it as flooring. [V&A, Powell Window Cash Book 1868-1872, p.116.] His design mixes opus sectile and glazed black glass tiles with porphyry and serpentine roundels to create a pavement combining the Medieval Italian influences of Cosmati work with opus Alexandrinum. Elaborate pavements would become a Jackson hallmark. This was his first. [Jones, ‘How “Oxford Jackson” began.]

Jackson was among its earliest champions and at Binsted in 1869 was the first to use it as flooring. [V&A, Powell Window Cash Book 1868-1872, p.116.] His design mixes opus sectile and glazed black glass tiles with porphyry and serpentine roundels to create a pavement combining the Medieval Italian influences of Cosmati work with opus Alexandrinum. Elaborate pavements would become a Jackson hallmark. This was his first. [Jones, ‘How “Oxford Jackson” began.]

Conclusion

St Mary’s is not the very ordinary small rural parish church of West Sussex it may seem. Historically and architecturally, it is an undervalued heritage asset that provides material evidence for significant parts of England’s history. In turn, the way these tie this church into the narrative of England’s past establishes valuable meaning for the local community. St Mary’s Binsted is special.

References

Primary

Victoria & Albert Museum, Archive of Art & Design, ADD/1977/1/55, Powell Window Cash Book 1868-1872

West Sussex Record Office, Par 22/4/4, Binsted Restoration Specification of Works, 1868

West Sussex Record Office, Par 22/4/6, Binsted Restoration Accounts, 1869

Secondary

‘The Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland’, www.crsbi.ac.uk

A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 5 Part 1, Arundel Rape: South-Western Part, Including Arundel (London, 1997)

D. Hadley, ‘OPUS SECTILE. Art from Recycled Scrap’ https://tilesoc.org.uk/publications/2018%20Opus%20Sectile%20Art%20from%20Recycled%20Scrap.pdf (2014)

M. D. W. Jones, ‘How “Oxford Jackson” began. Sussex church restorations in the 1860s’, Ecclesiology Today (vol. 59 forthcoming, 2021)

D. Park, ‘The Lewes Group of Wall Paintings in Sussex’, in ed. R. Allen Brown, Anglo-Norman Studies VI: Proceedings of the Battle Conference 1983 (John Wiley, 1984)

A. Saint, ‘The late Victorian church’, in T. Sladen & A. Saint (eds.), Churches 1870-1914 (The Victorian Society, 2011), 6-25

E. Williamson, T. Hudson, J. Musson & I. Nairn, The Buildings of England. Sussex: West (Yale University Press, 2019)